A common sight in China: The bicycle traffic signal. (Let's hope they don't become a thing of the past with China's increasing car-owner population.)

A common sight in China: The bicycle traffic signal. (Let's hope they don't become a thing of the past with China's increasing car-owner population.)Wednesday, May 23, 2007

Wednesday, May 16, 2007

Anhui in Photos

Since I've waited a month to post something on my trip to rural Anhui, I'm going to stick to posting photos for now. I've tried a couple of times to write about the crazy, unexpected, exciting and down right funny things that happened on that trip, but every time I sit down to write I don't have enough time to do it any justice.

Xikou, Anhui -- the base of operations for a weekend in the sticks -- your average, dusty, small town in China, population 20,000.

Xikou is famous for its green tea, which was being sold by the pile in a market right underneath the window of the room I slept in. I can say with authority that the market opens at around 3 a.m. with lots of honking, yelling and bell ringing.

One afternoon I started wandering around the old part of Xikou (what self-respecting Chinese town doesn't have a new "developing" portion with buildings decorated in fake Greek-like columns?). It reminded me somewhat of the old west -- and I love the hand-painted signs on every building.

After a stop at the opening ceremony for Xikou's "Tea Culture" Festival, we stopped by the local school to meet up with our host's family. My camera was spotted by a large group of drum-beating girls, who were very excited to have their pictures taken.

Our host, Xiao Wei, introduced us to his family, who let us stay in their homes for the weekend and were all around wonderful hosts. Behind the two kids is Lao Yezi, Xiao Wei's father.

I traveled to Xikou with my friend Eliot, fellow Nanjing resident and NYU alum. While we were in Xikou, some of the English teachers asked us to speak to their classes. Apparently their town doesn't get many foreigners passing through. The kids were nervous, but there was one hillarious kid up front who kept blurting out random English phrases like, "I'm 40 years old!"

On our second day in Anhui, Xiao Wei and his friends took us out into the wilderness to climb a mountain. Because I've been in China for a while I was expecting stairs and lots of tourists. But I was pleasantly surprised by our rough drive over a river bed to the base of the mountain. I knew that without a road it was pretty much guaranteed that hoards of tourists and their bull horn equipped tour guides would be no where in sight.

The climb was pretty rough, but we took breaks on the way.

At the top of the mountain was a magnificent view...

and a monastery.

We spent the night in the monastery and woke up early for a sunrise that never materialized because of fog.

We talked to this old monk who told us the story of the monastery's fate. He told us that the temple, which was once made of iron, was dismantled during the Great Leap Forward. Xiao Wei promised to help the monk by writing a letter to the government asking for compensation for the iron.

We started our trek early and got back to Xikou in time for one last lunch with Xiao Wei's family and friends.

Xikou, Anhui -- the base of operations for a weekend in the sticks -- your average, dusty, small town in China, population 20,000.

Xikou is famous for its green tea, which was being sold by the pile in a market right underneath the window of the room I slept in. I can say with authority that the market opens at around 3 a.m. with lots of honking, yelling and bell ringing.

One afternoon I started wandering around the old part of Xikou (what self-respecting Chinese town doesn't have a new "developing" portion with buildings decorated in fake Greek-like columns?). It reminded me somewhat of the old west -- and I love the hand-painted signs on every building.

After a stop at the opening ceremony for Xikou's "Tea Culture" Festival, we stopped by the local school to meet up with our host's family. My camera was spotted by a large group of drum-beating girls, who were very excited to have their pictures taken.

Our host, Xiao Wei, introduced us to his family, who let us stay in their homes for the weekend and were all around wonderful hosts. Behind the two kids is Lao Yezi, Xiao Wei's father.

I traveled to Xikou with my friend Eliot, fellow Nanjing resident and NYU alum. While we were in Xikou, some of the English teachers asked us to speak to their classes. Apparently their town doesn't get many foreigners passing through. The kids were nervous, but there was one hillarious kid up front who kept blurting out random English phrases like, "I'm 40 years old!"

On our second day in Anhui, Xiao Wei and his friends took us out into the wilderness to climb a mountain. Because I've been in China for a while I was expecting stairs and lots of tourists. But I was pleasantly surprised by our rough drive over a river bed to the base of the mountain. I knew that without a road it was pretty much guaranteed that hoards of tourists and their bull horn equipped tour guides would be no where in sight.

The climb was pretty rough, but we took breaks on the way.

At the top of the mountain was a magnificent view...

and a monastery.

We spent the night in the monastery and woke up early for a sunrise that never materialized because of fog.

We talked to this old monk who told us the story of the monastery's fate. He told us that the temple, which was once made of iron, was dismantled during the Great Leap Forward. Xiao Wei promised to help the monk by writing a letter to the government asking for compensation for the iron.

We started our trek early and got back to Xikou in time for one last lunch with Xiao Wei's family and friends.

Tuesday, May 15, 2007

Dateline: Pasadena, Calif. (or is that Mumbai, India?)

When fears arose a few years ago that journalism jobs would start to be outsourced to India, I thought it was the craziest thing I had ever heard. How could a guy in Mumbai report on the minutia of local politics in the United States? But, as seemingly crazy things tend to do, it became a reality, and it doesn't look like it's going to let up any time soon.

At the end of 2005 Reuters had already set up a 1,000+ media workforce in Bangalore, India that reports on Wall Street. Information about Wall Street aside -- after all, stock quotes can be analyzed as quickly on the other side of the globe thanks to our friend, technology -- I've still been skeptical that the trend would worm its way into local journalism.

But in a recent post in Information Week, blogger Richard Martin writes about PasadenaNow.com, which recently outsourced its city council reporting beat to two journalists in India.

So why is this happening? I think there are two reasons.

The first is obvious, it's the reason for outsourcing in all industries: cheap labor. The Indian journalists' combined salary is less than $20,000 a year -- a real coup for a local news organization that is probably like most local news organizations in the U.S. Local news organizations as I know them have one major goal: to constantly increase their already high profit margins (most U.S. newspapers make rake in a 20 to 30 percent profit margin as it is). One starting reporter at a small community newspaper makes all of $20,000 a year in more markets than most people would believe. Of course, as reporters gain experience, move onto bigger papers, or gain seniority, their salary increases some what. Either way, two reporters for the price of one starting reporter most likely has accountants in the media industry salivating. And with recent industry trends -- falling circulation, falling ad sales, reader traffic moving to the web, which most news companies have yet to find a way to make profitable -- outsourcing reporters must seem like a great way to keep profit margins high.

The second reason is less, well, nice: U.S. journalists are getting lazy. I know, I've been there, and I'm just as guilty as the next person of lazy reporting. We reporters make excuses for our lazy reporting -- being overworked, a small staff, no overtime budget. These reasons are valid, and I know writing ten or more stories a week will make anyone want to dash a few stories off without proofreading or confirming facts. But when the most local of local reporting jobs, the bread-and-butter of beat reporting, gets outsourced to India, it should be a wake up call. Journalists should be taking a second look at their own work. If we were producing unbeatable, compelling stories, our work couldn't be outsourced.

At the end of 2005 Reuters had already set up a 1,000+ media workforce in Bangalore, India that reports on Wall Street. Information about Wall Street aside -- after all, stock quotes can be analyzed as quickly on the other side of the globe thanks to our friend, technology -- I've still been skeptical that the trend would worm its way into local journalism.

But in a recent post in Information Week, blogger Richard Martin writes about PasadenaNow.com, which recently outsourced its city council reporting beat to two journalists in India.

Hatched by Web site publisher James MacPherson, who has the temerity to call local reporting "the routine stuff" that can be done from 9,000 miles away, this scheme has already attracted a legion of scoffers, most of them U.S.-based journalists, naturally. Speaking to The Associated Press, USC journalism professor Bryce Nelson called it "a truly sad picture of what American journalism could become."

So why is this happening? I think there are two reasons.

The first is obvious, it's the reason for outsourcing in all industries: cheap labor. The Indian journalists' combined salary is less than $20,000 a year -- a real coup for a local news organization that is probably like most local news organizations in the U.S. Local news organizations as I know them have one major goal: to constantly increase their already high profit margins (most U.S. newspapers make rake in a 20 to 30 percent profit margin as it is). One starting reporter at a small community newspaper makes all of $20,000 a year in more markets than most people would believe. Of course, as reporters gain experience, move onto bigger papers, or gain seniority, their salary increases some what. Either way, two reporters for the price of one starting reporter most likely has accountants in the media industry salivating. And with recent industry trends -- falling circulation, falling ad sales, reader traffic moving to the web, which most news companies have yet to find a way to make profitable -- outsourcing reporters must seem like a great way to keep profit margins high.

The second reason is less, well, nice: U.S. journalists are getting lazy. I know, I've been there, and I'm just as guilty as the next person of lazy reporting. We reporters make excuses for our lazy reporting -- being overworked, a small staff, no overtime budget. These reasons are valid, and I know writing ten or more stories a week will make anyone want to dash a few stories off without proofreading or confirming facts. But when the most local of local reporting jobs, the bread-and-butter of beat reporting, gets outsourced to India, it should be a wake up call. Journalists should be taking a second look at their own work. If we were producing unbeatable, compelling stories, our work couldn't be outsourced.

Monday, April 30, 2007

Happy Labor Day!

Reuters reported yesterday that 0.1 percent of children in Shanghai -- or one in 1,000 surveyed -- want to grow up to be "common workers." The story notes that while being a common worker used to be the ideal of the communist movement, values in China have changed since Deng Xiaoping proclaimed that "to be rich is glorious."

My question is: Who is that one kid in 1,000 who wants to be a common laborer? And by "common laborer" I mean the guys using pick axes to dig a hole to the sewer line in my neighborhood, the mine workers who disappear in coal mine collapses on a regular basis, the construction workers climbing up scaffolding 15 stories high without ropes, sometimes without shoes.

There's absolutely no sense in wanting to be a common worker in China. People do it out of necessity, not desire. I can't even imagine the children of common workers wanting to grow up to be common workers.

So that one child, does he really want to be a common worker? I imagine his parents are making him spend the holiday memorizing Marx while his friends are lounging on a beach in Hainan.

Newly rich Chinese are expected to spend the holiday, a time to celebrate the international labor movement, opening their wallets in far-flung destinations, reaping the rewards of higher paying jobs in the professions and financial sector.

My question is: Who is that one kid in 1,000 who wants to be a common laborer? And by "common laborer" I mean the guys using pick axes to dig a hole to the sewer line in my neighborhood, the mine workers who disappear in coal mine collapses on a regular basis, the construction workers climbing up scaffolding 15 stories high without ropes, sometimes without shoes.

There's absolutely no sense in wanting to be a common worker in China. People do it out of necessity, not desire. I can't even imagine the children of common workers wanting to grow up to be common workers.

So that one child, does he really want to be a common worker? I imagine his parents are making him spend the holiday memorizing Marx while his friends are lounging on a beach in Hainan.

So you want a new mom?

Continuing its trek through absurdity, the China Daily reports that a teenage girl in Dalian has been paying a classmate's aunt to pose as her mother at school meetings. Why? Because her mom lacked fashion sense.

Apparently being embarrassed by your parents when you're a teenager is universal. The story continues with a long, hilarious account of the ongoing mother-daughter troubles between Wang and Pingping, and attempts to place the "conflict" in some sort of social context:

Although Pingping attends school regularly, Wang never attended any of the parents' meetings because her daughter never told her about them. It was only when Wang called the school did she realize she had missed many meetings. Bewildered, Wang asked her daughter about what was going on, but Pingping's answer astonished her. "You made me lose face," she replied. "I have been asking a classmate's aunt to take part in it for me, 50 yuan (US$6.4) each time."

Apparently being embarrassed by your parents when you're a teenager is universal. The story continues with a long, hilarious account of the ongoing mother-daughter troubles between Wang and Pingping, and attempts to place the "conflict" in some sort of social context:

The generation gap in China has become so dramatic that parents who fail to catch up with the rest of the society could be abandoned by their children.That statement left me as bewildered as the mom with no fashion sense. Note to Chinese moms and dads: You better wake up and smell the Calvin Klein, otherwise you won't have an offspring to take care of you in your retirement years!

Sunday, April 29, 2007

Torch ignites controversy

I can't help it -- that headline was irresistible. Now that I don't write stuff like that for a living, I have to do it somewhere, so please forgive me.

I enjoyed a brief flurry of stories about the Beijing Olympics torch last week. After Beijing announced that the torch relay would include a climb up Mt. Everest, there was a little commotion caused by some Free Tibet protesters at base camp. It would have been little more than a blip on the news radar if it weren't for the fact that the activists, all American, were arrested.

But I found the wrangling over Taipei's position in the torch relay much more interesting. In the ongoing struggle between the PRC and Taiwan to project opposite images of inclusion/independence, Taipei will be the last stop on the international route/first domestic stop on the torch relay, or that's the plan so far. Officials in Taipei are said to have refused to be part of the domestic leg of the torch relay, but agreed to be a part of it if the torch entered from another country and exited to Hong Kong. Apparently that was international enough for Taiwan to accept and domestic enough for Beijing to accept.

That is, until Tsai Chen-wei, the head of Taiwan's Olympic Committee, decided that even that was unacceptable.

As a side note, not surprisingly the Chinese press includes Taipei on all its maps of the domestic relay.

Now while I see the concerns on both sides, the torch route is nothing more than a public relations battle, of which I believe Beijing has already won. Taipei's back and forth -- yes we accept, no we don't -- isn't helping their image or their credibility. To an international audience, the argument over placement in a torch relay can seem silly and irrelevant.

The 2008 Olympics has the potential to be a PR coup not only for Beijing, but also for Taiwan, human rights activists, the "Free Tibet-ers," big business -- and any individual or organization that has a stake in China. I, personally, am interested to see how the spin plays itself out over the next year.

Much has been written on the Everest protest in the blogsphere. Here are a few posts worth reading:

* Protests at the Roof of the World, Bad History and a new P.R. strategy for the P.R.C. from Jottings from the Granite Studio.

* An amusing post that makes its point well: Free Advice for the Free Tibet Crowd from Mutant Palm

* And an account from one of the Mt. Everest protesters himself in The Columbian.

I enjoyed a brief flurry of stories about the Beijing Olympics torch last week. After Beijing announced that the torch relay would include a climb up Mt. Everest, there was a little commotion caused by some Free Tibet protesters at base camp. It would have been little more than a blip on the news radar if it weren't for the fact that the activists, all American, were arrested.

But I found the wrangling over Taipei's position in the torch relay much more interesting. In the ongoing struggle between the PRC and Taiwan to project opposite images of inclusion/independence, Taipei will be the last stop on the international route/first domestic stop on the torch relay, or that's the plan so far. Officials in Taipei are said to have refused to be part of the domestic leg of the torch relay, but agreed to be a part of it if the torch entered from another country and exited to Hong Kong. Apparently that was international enough for Taiwan to accept and domestic enough for Beijing to accept.

That is, until Tsai Chen-wei, the head of Taiwan's Olympic Committee, decided that even that was unacceptable.

"This route is a domestic route that constitutes an attempt to downgrade our sovereignty," Tsai said. Tsai's comments contradicted an April 13 statement by another Taiwanese Olympic official, who said the island could accept a spot on the torch route that involved Hong Kong.

As a side note, not surprisingly the Chinese press includes Taipei on all its maps of the domestic relay.

Now while I see the concerns on both sides, the torch route is nothing more than a public relations battle, of which I believe Beijing has already won. Taipei's back and forth -- yes we accept, no we don't -- isn't helping their image or their credibility. To an international audience, the argument over placement in a torch relay can seem silly and irrelevant.

The 2008 Olympics has the potential to be a PR coup not only for Beijing, but also for Taiwan, human rights activists, the "Free Tibet-ers," big business -- and any individual or organization that has a stake in China. I, personally, am interested to see how the spin plays itself out over the next year.

Much has been written on the Everest protest in the blogsphere. Here are a few posts worth reading:

* Protests at the Roof of the World, Bad History and a new P.R. strategy for the P.R.C. from Jottings from the Granite Studio.

* An amusing post that makes its point well: Free Advice for the Free Tibet Crowd from Mutant Palm

* And an account from one of the Mt. Everest protesters himself in The Columbian.

Sunday, April 22, 2007

When life imitates textbook

rn

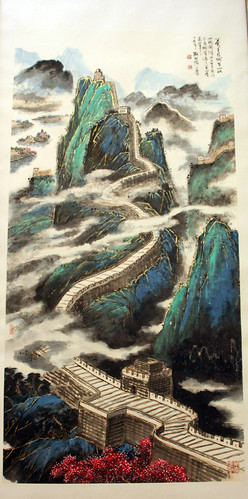

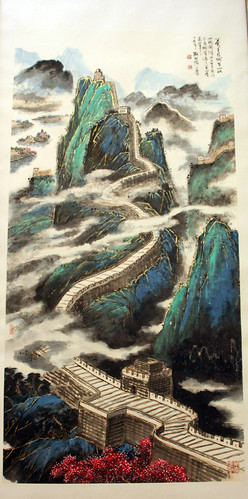

My view of the Great Wall on a trip to Badaling in March.

While I was reading a wonderful book called Spook: Science Tackles the Afterlife by Mary Roach (also the author of the equally fascinating Stiff: The Curious Lives of Human Cadavers), I experienced what one scientist who studies the afterlife described to Roach as a "dazzle shot."

You see, this scientist, Gary Schwartz -- a psych professor at the University of Arizona and the founder of a lab that does research on mediums, including Alison DuBois, the inspiration for the American TV series, Medium -- has asked dead people a lot of questions. And since Gary Schwartz is not himself a medium, he uses mediums to ask relatively mundane questions about the afterlife. Do you eat? Can you see me when I'm in the shower? He's also conducted studies that asked people to rate a medium's accuracy in describing a loved one. They had four rating options: hit, miss, questionable, or "dazzle shot" -- in other words, so accurate it was spooky.

Although my experience with the "dazzle shot" did not involve dead people, or the afterlife or mediums for that matter, I still think "dazzle shot" is the perfect phrase to describe the accuracy with which my Chinese textbook portrayed my very own life one morning not so long ago.

As usual, at 7:40 a.m. I walked downstairs to the bike parking area in front of my building. I tried to unlock my bike, but couldn't. I stood there and scratched my head for a second. Wait. That's not my bike. It's silver like my bike, but not mine. I have a different basket. I stood there gaping at the five or six bikes locked up in front of me. I didn't want to believe my bike wasn't there, so I just kept staring. When I realized how incredibly late to class I was going to be if I didn't immediately head for the bus stop, I snapped out of it. I had just bought that bike two weeks before. I seethed on the bus on the way to class -- it was the second time this year I had had a bike stolen.

I arrived 20 minutes late to class, opened my textbook to the day's lesson and started reading the text with the class. Halfway through I realized that the character Da Shan (hopefully no relation to the Canadian Da Shan of CCTV9) was living my life. In the text he explains to his friend that he's been having a lot of bad luck lately.

Here's a rough translation of the part of the text that would have made me check "hit" on a Gary Schwartz medium survey:

All of this of course means nothing. My textbook is about as psychic as the gold fish that swim around in a tiny bowl in my living room. It just shows the obvious: that bikes are stolen often enough in China to warrant a chapter in my textbook (the same textbook that had a chapter devoted to diarrhea and food poisoning). But just for a moment, before the "dazzle shot" wore off, I imagined Gary Schwartz starting a new study that measured language textbooks' psychic ability.

Maybe I'll be lucky enough to see something more like this on my next trip to the Great Wall.

My view of the Great Wall on a trip to Badaling in March.

While I was reading a wonderful book called Spook: Science Tackles the Afterlife by Mary Roach (also the author of the equally fascinating Stiff: The Curious Lives of Human Cadavers), I experienced what one scientist who studies the afterlife described to Roach as a "dazzle shot."

You see, this scientist, Gary Schwartz -- a psych professor at the University of Arizona and the founder of a lab that does research on mediums, including Alison DuBois, the inspiration for the American TV series, Medium -- has asked dead people a lot of questions. And since Gary Schwartz is not himself a medium, he uses mediums to ask relatively mundane questions about the afterlife. Do you eat? Can you see me when I'm in the shower? He's also conducted studies that asked people to rate a medium's accuracy in describing a loved one. They had four rating options: hit, miss, questionable, or "dazzle shot" -- in other words, so accurate it was spooky.

Although my experience with the "dazzle shot" did not involve dead people, or the afterlife or mediums for that matter, I still think "dazzle shot" is the perfect phrase to describe the accuracy with which my Chinese textbook portrayed my very own life one morning not so long ago.

As usual, at 7:40 a.m. I walked downstairs to the bike parking area in front of my building. I tried to unlock my bike, but couldn't. I stood there and scratched my head for a second. Wait. That's not my bike. It's silver like my bike, but not mine. I have a different basket. I stood there gaping at the five or six bikes locked up in front of me. I didn't want to believe my bike wasn't there, so I just kept staring. When I realized how incredibly late to class I was going to be if I didn't immediately head for the bus stop, I snapped out of it. I had just bought that bike two weeks before. I seethed on the bus on the way to class -- it was the second time this year I had had a bike stolen.

I arrived 20 minutes late to class, opened my textbook to the day's lesson and started reading the text with the class. Halfway through I realized that the character Da Shan (hopefully no relation to the Canadian Da Shan of CCTV9) was living my life. In the text he explains to his friend that he's been having a lot of bad luck lately.

Here's a rough translation of the part of the text that would have made me check "hit" on a Gary Schwartz medium survey:

Da Shan: Someone "rode away" on the bike I just bought, and until now he hasn't returned it.And here is where the "dazzle shot" comes in:

Ai De Hua: And you're still waiting for him to return it? (Read this with a sarcastic tone and the whole text makes much more sense).

Da Shan: Last week I went to the Great Wall with a friend. WhenThe week before that fateful lesson I had in fact been in Beijing and attempted to visit the Great Wall. And while I succeeded in making it to the well-touristed Badaling portion of the wall, I felt like the trip was such a failure that I should immediately start planning another trip to Beijing just so I could actually see the Great Wall the next time I visited. The weather, as it was on Da Shan's trip, was terrible, except even worse. It was snowing. And just like Da Shan, it wasn't snowing in Beijing when I left in the morning. It was a little overcast and grey, but I did not expect snow. The fog was so thick I could barely see 50 feet in front of me, so although I was standing on the Great Wall, I did not actually get to see the Great Wall.

we left the weather was so beautiful. As soon as we arrived, it started to rain really hard. We hadn't brought an umbrella and were completely soaked.

All of this of course means nothing. My textbook is about as psychic as the gold fish that swim around in a tiny bowl in my living room. It just shows the obvious: that bikes are stolen often enough in China to warrant a chapter in my textbook (the same textbook that had a chapter devoted to diarrhea and food poisoning). But just for a moment, before the "dazzle shot" wore off, I imagined Gary Schwartz starting a new study that measured language textbooks' psychic ability.

Maybe I'll be lucky enough to see something more like this on my next trip to the Great Wall.

Tuesday, April 10, 2007

Trouble in paradise

One of the best -- and most horrific -- travel experiences I've been lucky enough to have in China was a trip to Jiuzhaigou, a nature preserve in Sichuan Province. I'll never forget Jiuzhaigou's stunning beauty, crystal blue waters and stunning alpine scenery. I'll never forget being there with 20 thousand other people. I'll never forget the tour bus stops at stores that sold things like yak bone carvings, yak meat, costume jewelry, honey and tea.

One of the best -- and most horrific -- travel experiences I've been lucky enough to have in China was a trip to Jiuzhaigou, a nature preserve in Sichuan Province. I'll never forget Jiuzhaigou's stunning beauty, crystal blue waters and stunning alpine scenery. I'll never forget being there with 20 thousand other people. I'll never forget the tour bus stops at stores that sold things like yak bone carvings, yak meat, costume jewelry, honey and tea.And I'll never forget our tour guide, to whom someone mistakenly gave a microphone that she would use precisely as I was about to fall asleep. She woke us every morning before 6 a.m. She took us to restaurants that served only pickled vegetables and fatty pork. Oh, and did I mention the yak bone carving store?

We stopped at so many souvenir stores on the way to and from Jiuzhaigou that I lost count. After the first few I started to pretend I was asleep on the bus so I didn't have to go in and pretend to look at stuff I wasn't going to buy anyway. Little did I know that I was taking my life into my hands by ignoring my tour guide's only source of income.

According to a recent China Daily article about a disturbing attack by a tour guide -- who stabbed 20 people -- most tour guides in China aren't paid. Instead they earn a living by taking their clients to overpriced souvenir stands that will pay the guide a commission from every purchase made by a person in their tour group.

Xu Minchao, 25, was leading 40 tourists through Lijiang, a World Heritage-listed tourist destination in mountainous Yunnan province, on Sunday when he suddenly ran into a souvenir shop and demanded a knife, Xinhua said. "Not realizing the man was ready to kill, a girl in the shop gave him one and was stabbed immediately in the arm," Xinhua said.

The China Daily and the ever-entertaining Xinhua News Agency also mentioned the guide's "troubled" background.

Police were also investigating whether the attack was linked to an unhappy childhood, Xinhua said. "Xu ... broke down in tears when talking about his parent's divorce and how it overshadowed his childhood, according to local police," it said.

When I got back from Jiuzhaigou I had already made up my mind never to take another tour in China again. This story, not surprisingly, only cemented my bias against the Chinese tour group and its souvenir stops. I imagine that for the unlucky 20 tourists Lijiang, a nice little town also surrounded by stunning scenery, will forever be inextricably linked to a commission-hungry, knife-wielding tour guide who lost it over his childhood and, possibly, a yak bone carving.

Saturday, March 31, 2007

Three views of a restoration

Some photos from a recent trip to the Forbidden City in Beijing. More photos of Beijing are posted here, and I will be writing something about that trip soon.

Saturday, March 24, 2007

A sad day for Philippine journalism

Newsbreak, one of my favorite magazines in Manila, has gone to a web-only publication. (I'm biased, I contributed to the magazine while I lived there, and have enormous respect for the magazine's founders and editors.) While I'm trying to remain optimistic that the rumors of a possible underwriter for a continuation of the print version are true, I've also seen many small publications die a quick death after the shift to web-only versions.

It's difficult to describe Newsbreak's importance to Philippine journalism without a little context. It wasn't a news source with broad appeal, like the shows the network I worked for, ABS-CBN, produced. It was for the movers and shakers, the politicians, businessmen, investors, the intelligentsia.

Philippine journalism has a reputation -- and that reputation is not always a good one. Since Marcos fled the country in 1986, the country has enjoyed a free press – a pretty big accomplishment for an Asian nation. But as is often the case, when it comes to press freedom in the Philippines, the definition of "freedom" is not so clear.

For years the country held the unenviable title of the most dangerous country for journalists – and journalist murders still make the news on a regular basis. A lot of journalists in the Philippines brush the killings off when the journalists killed are not considered legit – they're on the take, they pay for radio air time to blast politicians they consider corrupt. But other victims are legitimate journalists working on stories about corruption, professionals who will not take money to stay quiet. In the 21 years since people power, only two people have been convicted of murder for journalist killings. So how free is a press where reporters, photographers, cameramen and editors are threatened and killed on a frequent enough basis as to make most people immune to the story?

But blaming only the party responsible for the killings or government inaction doesn't look at the full story. The Philippine press, if famous for being free, is also famous for being rife with corruption. Reporters who don't take money from sources are often considered stupid by their peers. Reporters and cameramen at the nation's largest stations are paid very little – and the bribes are considered a perk of being in the business – supplementary income that some of the employees desperately need. The act of taking money from sources even has a name -- "envelopmental" journalism -- named after the envelopes of cash handed to reporters.

Newsbreak's stories were well-researched, thoughtful, agenda-setting pieces in a sea of one-source newspaper stories with bizarre headlines and brief TV news clips littered with inaccuracies. The editors and writers I met at Newsbreak were motivated and passionate. More important, they were outspoken about and have denounced the unsavory practices of the Philippine press. They've been threatened, they've been taken to court on libel charges, they've been arrested, and, according to their Web site, they've been working for a while without pay. I'm hoping they can keep up their passion and dedication long enough to resurrect the print publication -- it would be a shame to lose such an important contribution to the Philippine press.

******

Here's more commentary on Newsbreak's shift to a web-only publication。

It's difficult to describe Newsbreak's importance to Philippine journalism without a little context. It wasn't a news source with broad appeal, like the shows the network I worked for, ABS-CBN, produced. It was for the movers and shakers, the politicians, businessmen, investors, the intelligentsia.

Philippine journalism has a reputation -- and that reputation is not always a good one. Since Marcos fled the country in 1986, the country has enjoyed a free press – a pretty big accomplishment for an Asian nation. But as is often the case, when it comes to press freedom in the Philippines, the definition of "freedom" is not so clear.

For years the country held the unenviable title of the most dangerous country for journalists – and journalist murders still make the news on a regular basis. A lot of journalists in the Philippines brush the killings off when the journalists killed are not considered legit – they're on the take, they pay for radio air time to blast politicians they consider corrupt. But other victims are legitimate journalists working on stories about corruption, professionals who will not take money to stay quiet. In the 21 years since people power, only two people have been convicted of murder for journalist killings. So how free is a press where reporters, photographers, cameramen and editors are threatened and killed on a frequent enough basis as to make most people immune to the story?

But blaming only the party responsible for the killings or government inaction doesn't look at the full story. The Philippine press, if famous for being free, is also famous for being rife with corruption. Reporters who don't take money from sources are often considered stupid by their peers. Reporters and cameramen at the nation's largest stations are paid very little – and the bribes are considered a perk of being in the business – supplementary income that some of the employees desperately need. The act of taking money from sources even has a name -- "envelopmental" journalism -- named after the envelopes of cash handed to reporters.

Newsbreak's stories were well-researched, thoughtful, agenda-setting pieces in a sea of one-source newspaper stories with bizarre headlines and brief TV news clips littered with inaccuracies. The editors and writers I met at Newsbreak were motivated and passionate. More important, they were outspoken about and have denounced the unsavory practices of the Philippine press. They've been threatened, they've been taken to court on libel charges, they've been arrested, and, according to their Web site, they've been working for a while without pay. I'm hoping they can keep up their passion and dedication long enough to resurrect the print publication -- it would be a shame to lose such an important contribution to the Philippine press.

******

Here's more commentary on Newsbreak's shift to a web-only publication。

Tuesday, March 13, 2007

Staying ahead of the curve

In October I decided it was time to take the GRE and apply to graduate school. I am mercifully in the decision making portion of a long test and application process that ate up much of my time during the fall semester. I thought registering for the GRE would be easy; after all, the university students I taught in Hangzhou in 2004 were all taking the GRE to try to get into graduate schools in the United States. It couldn't be that difficult to register for the test in China.

But, as things sometimes are when you live in Asia, it was quite difficult. First I registered for the test in Hong Kong because the Nanjing registration deadline had already passed. I soon found out that I could only take part of the test in Hong Kong, the essay portion, and would have to wait until May to take the rest of the test. That was just too late. By May graduate schools would have already decided on their incoming class. So I did the next best thing I could think of: I registered for the test in Manila, where I could take the full GRE in one four- to five-hour sitting. I could have gone to Bangkok to take it, but figured I could wrap in a long weekend with friends in the Philippines.

Why is it so much easier to take the GRE in Manila or Bangkok than in China? Cheating. And it's not just cheating on the GRE -- it's every test you can think of. According to a brief in the New York Times about SAT scores being cancelled in South Korea (apparently China isn't the only country that keeps ETS test writers up late), in the early 90s around 10,000 TOEFL test scores were cancelled in China because of cheating.

For those of you who teach or have taught in China, this comes as no surprise. I often devised complicated methods for preventing cheating during midterm and final exams. In my writing classes I learned (the hard way) to take in-class writing samples from my students to make spotting plagiarism a little easier.

I'm not quite sure why the Philippines isn't also blacklisted by testing services. Last year the Philippines' nursing board exam was leaked. Forty-two thousand potential nurses had taken the test, and around 17 thousand passed. Some thought candidates should retake the test; others did not think it was necessary. But perhaps the Educational Testing Service, the gatekeeper of the GRE and SAT, among many other tests, had not had many problems in the Philippines. Or if they did, perhaps it's a question of volume: I would guess that the number of Chinese students taking ETS tests far outnumber Filipino students.

Still -- like the DVDs that make their way to a Chinese pirating company well before it leaves theaters -- copies of standardized tests always manage to make their way to Asia, and no doubt other enterprising students around the world. Cheating students definitely keep ETS test writers employed. In an attempt to stay ahead of the curve, they're probably writing multiple tests each month, and, not surprisingly, being beaten at their own game by the students they're supposed to test.

But, as things sometimes are when you live in Asia, it was quite difficult. First I registered for the test in Hong Kong because the Nanjing registration deadline had already passed. I soon found out that I could only take part of the test in Hong Kong, the essay portion, and would have to wait until May to take the rest of the test. That was just too late. By May graduate schools would have already decided on their incoming class. So I did the next best thing I could think of: I registered for the test in Manila, where I could take the full GRE in one four- to five-hour sitting. I could have gone to Bangkok to take it, but figured I could wrap in a long weekend with friends in the Philippines.

Why is it so much easier to take the GRE in Manila or Bangkok than in China? Cheating. And it's not just cheating on the GRE -- it's every test you can think of. According to a brief in the New York Times about SAT scores being cancelled in South Korea (apparently China isn't the only country that keeps ETS test writers up late), in the early 90s around 10,000 TOEFL test scores were cancelled in China because of cheating.

For those of you who teach or have taught in China, this comes as no surprise. I often devised complicated methods for preventing cheating during midterm and final exams. In my writing classes I learned (the hard way) to take in-class writing samples from my students to make spotting plagiarism a little easier.

I'm not quite sure why the Philippines isn't also blacklisted by testing services. Last year the Philippines' nursing board exam was leaked. Forty-two thousand potential nurses had taken the test, and around 17 thousand passed. Some thought candidates should retake the test; others did not think it was necessary. But perhaps the Educational Testing Service, the gatekeeper of the GRE and SAT, among many other tests, had not had many problems in the Philippines. Or if they did, perhaps it's a question of volume: I would guess that the number of Chinese students taking ETS tests far outnumber Filipino students.

Still -- like the DVDs that make their way to a Chinese pirating company well before it leaves theaters -- copies of standardized tests always manage to make their way to Asia, and no doubt other enterprising students around the world. Cheating students definitely keep ETS test writers employed. In an attempt to stay ahead of the curve, they're probably writing multiple tests each month, and, not surprisingly, being beaten at their own game by the students they're supposed to test.

Friday, March 9, 2007

Lantern Festival

The night before school started a few friends and I decided to brave the Lantern Festival crowds at Fuzi Miao. We arrived at about 8 pm, which was our first mistake. By the time we got there, it was so crowded that a shoulder-to-shoulder line of police was not allowing anyone to enter. Luckily there were so many people that even the outskirts of Fuzi Miao were incredibly festive.

A proposal

I was mercifully nearing the end of the daily hour-and-a-half of pain when the 11-year-old Korean boy I tutor, Yang Hee, looks up at me and asks me what I thought was a sweet and innocent question.

"Christina, do you like me?"

"Of course, Yang Hee," I said.

I shouldn't have encouraged him. I could see the wheels turning in his head, searching for some newly acquired English he was hoping to practice on me. Finally he spit it out.

"Do you is want to marry me?"

I laughed. "Sorry, Yang Hee, I think you should find someone your own age."

*****

The same night during the cab ride home I'm in the middle of sending a text message to a friend about my recent "proposal" when the cab driver asks me how old I am.

This is always an invitation to further questions about my life, particularly the lack of husband and child. I thought for a second about lying to him, but instead told the truth. As if cued by some invisible director in the back seat of the car, he promptly asked me how I can be 27 years old and not married. I'm asked this often enough in China to have a few stock answers that I rotate between – usually something about living abroad for a long time or not meeting the right person yet or that "foreigners" often get married later.

I think it's because most of my friends in Nanjing are younger than me, but this question, which usually does not bother me, made me suddenly feel like I should be living in an apartment overrun by cats. I feel like this question in China has a lot to do with the age of the person you're talking to. My 40-something cabdriver came from a time when getting married young was just what you do. The generation born in the late 70s and 80s generally has a different attitude toward marriage. Though I meet plenty of young women who got married in their early 20s, I also meet many people who are putting off marriage for a career, or just because they can, because they have more choices. But they still have to deal with their parents – about the same age as my cab driver – asking the same questions.

"Christina, do you like me?"

"Of course, Yang Hee," I said.

I shouldn't have encouraged him. I could see the wheels turning in his head, searching for some newly acquired English he was hoping to practice on me. Finally he spit it out.

"Do you is want to marry me?"

I laughed. "Sorry, Yang Hee, I think you should find someone your own age."

*****

The same night during the cab ride home I'm in the middle of sending a text message to a friend about my recent "proposal" when the cab driver asks me how old I am.

This is always an invitation to further questions about my life, particularly the lack of husband and child. I thought for a second about lying to him, but instead told the truth. As if cued by some invisible director in the back seat of the car, he promptly asked me how I can be 27 years old and not married. I'm asked this often enough in China to have a few stock answers that I rotate between – usually something about living abroad for a long time or not meeting the right person yet or that "foreigners" often get married later.

I think it's because most of my friends in Nanjing are younger than me, but this question, which usually does not bother me, made me suddenly feel like I should be living in an apartment overrun by cats. I feel like this question in China has a lot to do with the age of the person you're talking to. My 40-something cabdriver came from a time when getting married young was just what you do. The generation born in the late 70s and 80s generally has a different attitude toward marriage. Though I meet plenty of young women who got married in their early 20s, I also meet many people who are putting off marriage for a career, or just because they can, because they have more choices. But they still have to deal with their parents – about the same age as my cab driver – asking the same questions.

I'm back

After a few months without blogging, I've decided to start again. I'll admit, I missed it, and when I went home in February I had a few requests to start one up again. I named the blog "Letters from Asia" because I'll probably stray from stories about the country I'm currently living in, China. Although I expect that most of what I write about will be about China and my experiences as a student in Nanjing, I'll also probably write now and again about the Philippines, a country I grew to appreciate and love during the year I spent there working at a television station.

For those of you who stumble upon my blog who aren't members of my family or my friends, here's a little about me: I'm an American studying Chinese at Nanjing Normal University for a year. About a year and a half ago I left what some might consider to be a"stable" job with a community newspaper in Lake Tahoe to move to Manila to work for a television station undergoing enormous change. When my year in Manila was up, I moved back to China to continue what I started a few years ago when I taught English in Hangzhou.

I love to get comments from people, especially those who are more insightful than I am (and there are plenty of you out there), so I'm looking forward to hearing from all of you.

For those of you who stumble upon my blog who aren't members of my family or my friends, here's a little about me: I'm an American studying Chinese at Nanjing Normal University for a year. About a year and a half ago I left what some might consider to be a"stable" job with a community newspaper in Lake Tahoe to move to Manila to work for a television station undergoing enormous change. When my year in Manila was up, I moved back to China to continue what I started a few years ago when I taught English in Hangzhou.

I love to get comments from people, especially those who are more insightful than I am (and there are plenty of you out there), so I'm looking forward to hearing from all of you.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)